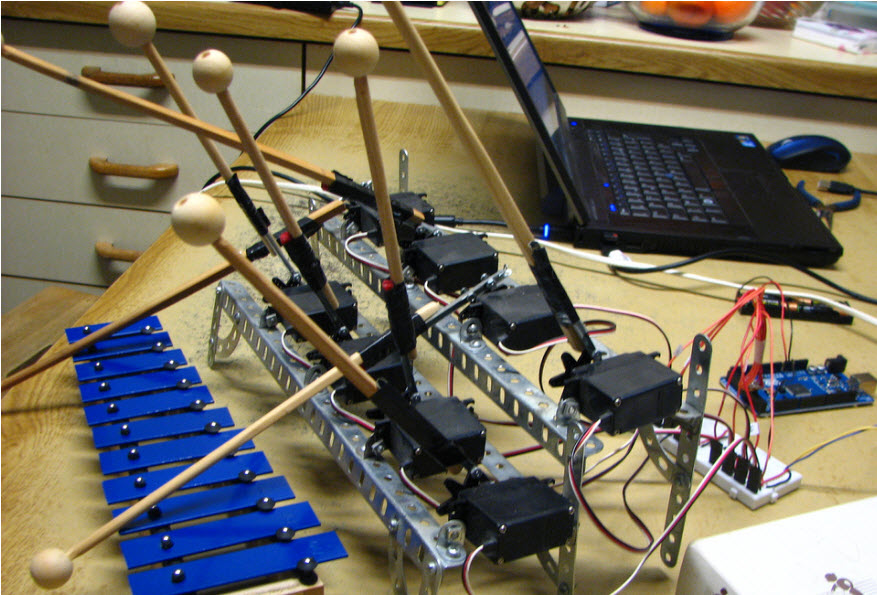

CC Image used with permission.

By William Hertling, Senior Software Engineer

HP Vancouver

Abstract

The microservice approach to building large web applications has risen in popularity due to the numerous advantages it has for scaling, deployment, and functional decomposition.

As a result, proposing a web service that’s not based on microservices is practically sacrilege these days. And worse, advocating for not writing tests earns dirty looks from coworkers as if I had suggested drinking and driving without seatbelts, and with the airbags disabled.

Yet microservices and test-driven development have costs associated with them. They make sense for most large-scale, mature applications, but there are situations in which they don’t make sense. In fact, using microservices too early can create wasted work, decrease developer efficiency, and negate one of the primary benefits of early prototyping: namely, faster learning. To a lesser extent, test-driven development suffers from some of the same tradeoffs.

Context

Over the last five years I have worked on a team of seven to ten developers, using Agile practices to develop web services and applications. We work in Rails, deploy to Amazon Web Services, and own everything ourselves. Almost everything we develop is either a RESTful API service, or is a larger application wrapped around RESTful APIs.

Like many teams, we build and deploy functional prototypes. Some of these prototypes turn into revenue-generating products, but the majority do not. Most of what we do is develop a concept just far enough so that we can better evaluate the technical feasibility, validate management support, learn more about the underlying principles, and/or test the value proposition with end-users.

At some point, the project is terminated or handed over to others. Even a terminated project will often have applicable knowledge or technology that gets rolled forward to a future project or shared with other teams.

Lightbulb Moment

For a couple of months, I worked on a small – but not trivial – Rails application outside of my day job. I implemented users and passwordless logins and had about a dozen interrelated database tables. I deployed to Heroku, and supported a few dozen active beta users.

Working on my own, I noticed a curious thing. Even though I had very little time for my hobby project between my day job, my writing, and my kids, I was somehow still making faster progress at home than my entire team was making at work.

I work with talented, experienced developers, so the problem wasn’t due to the people. There had to be some sort of friction that was holding the team back. What was it?

The first clue came when I was implementing a new Rails model in our current work project. I should have been able to rely on the Rails ORM, ActiveRecord, using its built-in associations functionality to find, create, and manage connected instances of models. But because we were using a microservice architecture, the associations I needed to use were actually RESTful relationships. Instead of merely referencing the association, and letting ActiveRecord take care of the necessary SQL interactions, I was writing multiple lines of code every time I needed to load instances of another model.

Sometimes I’d need those instances according to new criteria that hadn’t been used before. Instead of merely providing the relevant criteria via the ORM query interface, I’d have to switch projects, go add those criteria to the RESTful API on one service, write a bunch of tests to ensure the functionality was correct, then go back to the other service to use the new query interface.

What should have taken seconds ended up taking an hour and derailing my progress on the user feature I should have been working on.

The Microservice Argument

I made the case to the rest of the team that using a microservice architecture was vastly increasing the amount of work we needed to do, perhaps by a factor of 2x, and thus slowing down our progress by an equivalent amount and robbing our team of the ability to be the consistent high-performers we had been in the past.

Not surprisingly, they objected. We couldn’t possibly consider going back to a monolithic architecture, because everyone knows microservices are better. Able to deploy each microservice to exactly the best kind of instance for the work that it does. Better division of work, and better encapsulation. More scalable, and independently scalable.

These are all good arguments, but they don’t apply to prototypes. We don’t need independent deployment and scaling. We don’t need to use different, highly specialized instance types when the whole application can easily fit on just about any instance. We don’t need to spread the load out across multiple machines. We don’t need to encapsulate teams of developers from each other.

What we do need is to get features out faster, to deploy quickly and easily to the simplest stack that will support what we need for our prototype, and to minimize overhead that slows us down.

My coworker was concerned that failing to implement the application as a collection of microservices from the start would lead to a poor architecture down the road. But good architecture design is separate from how the application is actually built. We can design models with minimal and well-regulated interfaces and then choose to implement them all within a single monolithic application. If some component of the application later merits being an independent microservice, it can be cleanly extracted later.

In fact, we had done just that in a single sprint on an earlier project. Incurring a week of work to extract a microservice later makes sense if doing so saves many weeks of work early on.

This is especially true in environments where many prototypes are being built, only some of which will survive to become ongoing production applications. In that case, it is preferable to optimize developer effort by implementing only that which is necessary to reach a decision point, and avoiding the overhead associated with more production-oriented concerns.

Test-Driven Development and Further Efficiencies

If microservices add complexity and friction when applied early in the project, then maybe test driven development also warrants concern. In the early days of my hobby project, I operated just fine without tests, even though I knew I was incurring technical debt.

It often takes more time to write tests than it does to implement the actual functionality, so I was saving at least half of my development time by foregoing tests. When you combine this with the advantages of using a simple monolithic application, this is roughly a 4x improvement in efficiency.

Software developers know how long it takes to get into the groove, and there are few things worse than being interrupted when you’re in the midst of a big feature.

Taking work out shortens the amount of time a given feature requires to be developed. With a 4x gain, something that might take eight hours can be done in as little as two. It is much easier to find two focused hours than eight. In an eight hour day at work, I’m interrupted at least once for lunch, once or twice by meetings, and several more times by colleagues. However, two hours I can carve out. So there’s an additional gain in efficiency that comes from keeping tasks small so they can be implemented quickly in one burst.

Going without testing will often be faster for the first few weeks, especially when working solo or on a small team. If you can reach a decision point quickly, then it may be worth foregoing tests, whether TDD or TAD, in order to reach that decision as quickly as possible. After all, if you ultimately decide not to use a given feature or approach, then any tests written for it would be wasted effort.

On the other hand, few things can accrue technical debt faster than not writing tests, because as complexity grows, the time spent in ad-hoc testing or recovering from bugs caught late in the process will dwarf any gains in efficiency in the early days. In particular, it’s especially important to make sure key functionality, such as core algorithms, behave as expected. Often, testing the user interface and flow can be deferred without too much risk until later in the project, once the UI has been user-tested.

Conclusion

Depending on the type of work you’re doing, and the percentage of prototypes that makes it to production, it can make sense to use a simpler monolithic architecture early in the project lifecycle rather than to jump right to a microservice architecture. The same argument can be made for deferring automated tests, although this only makes sense in the very earliest days, and only when there is a reasonable chance the code may be abandoned. Combining these techniques can shorten implementation tasks to the point where even more efficiency and momentum is gained by avoiding interruptions and other distractions mid-implementation.

William Hertling is a senior software engineer working on 3D printing software solutions. Outside of HP, he is a science fiction writer. His most recent novel, Kill Process, about a computer hacker who hunts down domestic abusers and kills them, explores data ownership and privacy issues. Brad Feld, managing director of Foundry Group and author of Venture Deals, called Kill Process “Awesome, thrilling, and creepy: a fast-paced portrayal of the startup world, and the perils of our personal data and technical infrastructure in the wrong hands.”